by Jesse Reyes

Cambridge Associates just announced a “New Method to compare public market and private market returns”. see press release

Comparing private equity returns to public market returns has always been problematic since private equity has been firmly ensconced in the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) while the public markets have been measured by time-weighted returns – the two returns are incommensurable directly (more on that in a later post)– although that doesn’t stop the financial and mainstream press from doing just that-much to my (as well as that of many of my quant’s brethren’s) chagrin.

The Cambridge Associates method is the latest in a series of alternative approaches to direct public/private market comparison which first surfaced about 20 years ago.

There is tremendous amount of literature by both academics and practitioners regarding the problems that the IRR creates when trying to compare the returns of public markets and private markets. We’ll cover those problems in future posts but for now let’s concentrate on what the industry has done to address this conundrum.

After all, a pension fund will have investments in several asset classes. How can they perform an apples-to-apples performance comparison if the methods used by the private equity industry are incommensurable to methods used in other asset classes.

So with the Cambridge Associates press release, I thought the subject deserves a bit of a history lesson.

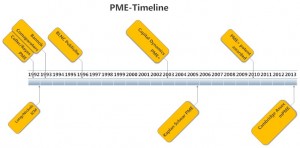

Act I: Early 1990s- Birth of PME

(actually multiple births)

Scene I: Jeremy in Madrid

In June 1992, I was attending EVCA’s Venture Symposium in Madrid. In those days the conference was a much more intimate affair compared to EVCA’s later large-scale symposium. Some of the quaintness of the era included real-time translation of speaker panels into multiple languages. I remember a whole bank of translators in the back of the room during my panel discussions. I know my presentation on performance statistics must have given the translators fits. For some fun – try translating “vintage year returns net of fees and carry to investors” or “skewness measured by kurtosis” into Spanish three times real fast in real time.

At one of the lunch meetings, I met for the first time someone who would become one of my closest professional friends – Jeremy Coller.

Over one the lunch breaks he and I discussed benchmarking, returns and related data – real nerdy stuff, but I was glad to find someone who had been thinking about these issues as much as I had and was extremely gratified to find someone else who thought the current state of returns and performance measurement made public market comparables difficult.

Jeremy told me that he thought he’d solved the public/private market comparison conundrum. I would learn it not be the first time we’d have a conversation where Jeremy told me that he’d solved some thorny problem and he usually had a novel approach to doing just that. For example, I still carry his IRR calculation card in my wallet though I understand it’s now available as an app.

His thought experiment regarding public market went a bit like this (pardon my paraphrasing):

“Rather than trying to calculate a time-weighted return for the private equity industry” (as we all had been trying to do), “let’s create an IRR for the public markets.”

To do this, Jeremy proposed:”Let’s say that we invested the capital we committed to a venture capital fund into a public market index and then compound those investments forward to the end of its life. That would give you a synthetic ending NAV that you can use with the original cashflows to create an ‘IRR of public markets’ that you could compare to the IRR of a fund.

It was an intriguing idea and I had to put some pencil to paper, but I had access to the data to test it. So back at the “lab” at Venture Economics we took Jeremy’s thought experiment, made an algorithm out of it and then planned to publish it as the first public market equivalent (PME as I coined it) benchmark in our investment benchmark report series at Venture Economics.

Scene II: Austin in Austin

During our testing, I discovered an unpublished white paper that was forwarded to me by a limited partner client which was written by two other close professional friends, Austin Long and Craig Nickels who were the private equity investment managers at the University of Texas Investment Management Company (UTIMCO) in Austin, Texas.

Their unpublished paper, A Method for Comparing Private Capital Internal Rate of return with Public Market Index Returns , (see this link for a later fully-developed version) was developed in 1992 or 1993. It described a method called the “Index Comparison Method” (ICM) which invested the capital called by a fund into a public market index – then compounded the results forward to the end of the fund and then calculated an IRR on the resultant NAVs and original cashflows. Though unpublished, Austin and Craig by their own admission, presented this paper to at least 50 different private equity conferences and workshops and thus the method became ubiquitously known.

Scene III– Meanwhile in London

To add to the people thinking about this problem, Bannock Consulting in London was a group working on UK and European performance statistics for the BVCA and later for the EVCA. They were developing their own method to compare public and private market returns which “invested capital into an index and calculated IRRs from that resultant investment”. They called their approach “Comparators”.

Thus by 1995 we had three “identical” methods for solving the problem of comparing public/private markets. For publication we called these methods “Public Market Equivalent” or “PME”. Benchmarks based on this PME methodology were published for the first time in 1996 in the Venture Economics Investment Benchmarks Report.

Now what to call this new metric? At Venture Economics we’d already decided PME was the term we’d use commercially. But how to give credit to all the contributors to the body of knowledge? It wasn’t a Nobel Prize, but we felt it was necessary to give proper attribution.

Would it be Coller/Reyes PME, Long/Nickels ICM, Bannock/BVCA/EVCA Comparators? Giving credit where it’s due we settled for less self-aggrandizement and published the first public/private benchmarks under the name Bannock, Long, Nickels, Coller PME (BLNC)

Act II: Trouble in Camelot

All was well with the world– contributors got attribution; investors had better tools to compare public and private equity markets, but then surfaced a mathematical problem.

While all three methods gave you the same result, mathematically the three approaches actually had different algorithms and approaches.

What some researchers, including Austin and Craig, noticed using this original PME approach, was that in some cases, returns in the private equity industry could so dominate the public markets that the only way you can reconcile the difference is to “short” the public markets.This occurred because you could distribute so much in proceeds in a successful private equity fund to turn the synthetic NAV negative. This led to unstable and unintuitive results..

Austin and Craig, among others, had noticed this anomaly, so back to their own lab they went, and then adjusted their method a bit and published an augmentation called the “Alternative Index Comparison Method” (AICM).. This ostensibly solved some of the attendant instability problems. But the AICM never got as much press or usage as the original ICM/PME formulation.

But for years, the ICM/PME or its derivatives was the dominant method for comparing public /private market returns when practitioners needed to do such things.

Scene IV: Zug Rocket Science

But the world wasn’t sitting still. Thomas Kubr and Christophe Rouvinez at Capital Dynamics – a firm who at the time I called the “rocket scientists” of the private equity world because of their quantitative focus toward private equity investment, had been working on another method to deal with this mathematical dominance/negative NAV problem.

Their method which they called PME+ was formulated in 2003 or so. Their approach was novel. See a VCJ article authored by Mr Rouvinez which applies the method.

Note that the original PME formulation worked by making the cashflows in the public and public market equivalent in order to derive a synthetic NAV which was allowed to fluctuate.

The PME+ instead, makes the NAVs between the public private market equivalent and used a share-unit method to acquire and distribute investments and proceeds and by a neat scaling trick balanced the shares so that the mathematical dominance problem is elegantly dealt with.

This was novel enough that Capital Dynamics was subsequently granted a US patent in 2010 for the method. (#7,698,196 if you want to look it up).

If there are any inherent perceptual issues withe PME+ which have affected widespread adoption they are probably summarized as:

- Since the NAVs between the public and private markets are equated to calculate the PME+ metric, and the cashflows are scaled in proportion, as time marches forward the NAVs will change and thus the historical cashflow scale factors will also change. Thus the synthetic cashflow sequences from one measurement period to the next will be dynamic. While this doesn’t create a calculation problem per se, it does make measurement periods difficult to reconcile and compare without having all the underlying historical data.

- Since the method is patented, it is difficult to apply this method without some sort of licensing arrangement.

Scene V – Academics take interest

Academics got into the mix as well. Steve Kaplan of the University of Chicago and Antoinette Schoar of MIT published their seminal academic paper “Private Equity Performance: Returns, Persistence and Capital Flows” written in 2004 but published in 2005 in the Journal of Finance.

In that paper, which may have been the first academic treatise to address the public/private comparison problem, Kaplan and Schoar created a method which they also called PME but which results not in an annualized return like an IRR but instead results in a synthetic multiple like a investment multiple similar to the TVPI used in the private equity industry.

Mathematically, the Kaplan/Schoar PME is equivalent to the methods in the aforementioned Coller/Reyes, Long/Nickels, Bannock/BVCA PME methods– see Austin Long demonstrated this in an unpublished monograph however the result is a ratio rather than a return. However in recent years, Austin Long has developed a method to convert the K&S PME to a quasi-time-weighted return.

But algorithmically K&S is probably closest in method to the original Coller/Reyes PME implementation.

Conceptual Issues that arise with the original K&S PME include:

- While the method is always calculable, it still mathematically shares the negative NAV problem with the original PME. K&S PME elegantly deals with this issue by focusing on the inflow/outflows and ignoring the NAV. However, you are still left with the subtle conceptual issue of distributing more than you have on hand when PE dramatically outperforms the market.

- It provide a scale-less ratio to compare public to private returns on a total return basis, but no annualized return that takes the time value of money into account.

Act III: Now another family member

Which is why the new approach announced by Cambridge Associates is interesting. Their press release noted that their proprietary method is patent pending. Their new method is called the Modified Public Market Equivalent (mPME).

According to a recent discussion with the principal researchers at Cambridge Associates, they did not develop this new method in a vacuum nor develop it to simply put their PME hat in the ring

They have a sophisticated client base which continually ask challenging questions regarding public market comparison to private markets and have expended considerable resources in either using traditional methods or trying to find new ways to make that comparison.

For years they adopted the traditional ICM/PME approaches but like other practitioners were not happy with the anomalies previously discussed. Given that the PME+ method is patented by a firm that could be viewed as a potential competitor, they did a tremendous amount of research and gave much thought on how to solve the problem independently.

They freely admit that while no method is perfect, bullet-proof, or flawless, if they could add to the thought leadership of this particular problem with a new method, they could serve both their clients and the industry well.

Given the access to the fund level cashflow data that they have compiled over the years, they have the ability to test many of theirs and other researchers ideas.

Their goal with this new method is four-fold:

- Develop a methodology that will provide consistent results at different levels of aggregation and across asset classes.

- Like most of the other industry methods, take the time value of money into account

- Minimize the number of assumptions in order to create a parsimonious model

- Provide another way of dealing with the negative NAV/mathematical dominance issue.

So how do they accomplish this. Here is an rough and brief overview of their method:

- Their approach (similar to others) is to create a synthetic NAV by investing and compounding those investments in a public market.index.

- However their approach is novel in the following respect: While they use the nominal capital contributions (paid-in capital) to purchase index shares, the distribution is not an automatic sale of of the index like the original PME or the K&S PME formulation. The distribution is scaled in proportion to the return of the fund and the capital available such that it can never exceed the capital available for distribution thus avoiding the negative NAV problem.

- Thus this method creates a hybrid nominal and synthetic cashflow/NAV stream that can be used to calculate public market analogs for IRR and for the various multiples and other ratios that the industry uses. In that regard, it combines attributes of the various traditional methods plus adds attributes of the conceptual scaling method that PME+ uses.

What issues can we identify with this particular method. We don’t have access to the exact method or algorithms yet so we have to speculate a bit but expect that the issues include:

- Like PME+, the distribution scaling factors appear to be dynamic as time moves forward from measurement period to measurement period. Again not a flaw but could create the perception that the method is “complicated”

- Like the other methods, it puts public markets in context of the private markets not the other way around. More on this issue below in the summary.

- Like Capital Dynamics, Cambridge Associate has a patent application pending thus making commercial adoption contingent on some formal arrangement.

We hope to test the results of this new method against the other methods in Part II of this series.

The FAQ for the Cambridge Associates mPME can be found at http://goo.gl/0jPQqK starting at question #23.

Act IV: Do we need another method?

While I generally endorse PME methods even when there are other industry statistics available, there are a few issues all these methods share.

- Even though some methods are now twenty years old and have been implemented in some mainstream portfolio management packages, and have been even adopted in the latest GIPS guidelines on private equity performance, they are still not ubiquitous enough to replace the traditional benchmarks that the industry uses.

- There is no guarantee that the various methods will give you the same result. Just as funds can “shop vintage years”, they may be able to “shop PME” to show how their private equity performance dominates public markets. This is not a problem with the methods themselves but a problem in how the industry applies them.

- Choice of an underlying public index use in the PME isn’t standardized. Should venture funds use NASDAQ as that index composition most likely mirrors the portfolio companies they invest in? Should buyouts choose the S&P500 or maybe a broader market index? Benchmark choice is a topic for another day.

- These methods have been implemented to compare private equity with public equities. It still doesn’t give limited partners a metric they can use to effectively compare private equity with other asset classes outside of the public markets. With these PME tools, you could compare private equity to public markets, alternative assets to public markets, real estate investments to the public markets, but you can’t directly compare these asset classes against each other. While you could use the delta between these public market comparisons to make some “intuitive” indirect comparison between these disparate investments, it could give misleading or specious comparisons. Alternatively, while you could compare a limited partner’s private equity investments to a bond index, real estate index etc. that is not the same as comparing a pension funds’ private equity portfolio returns to its own real estate holdings, bond investments or other alternative assets without either calculating an IRR for those holdings or comparing time-weighted private equity returns to those assets.However, both of these latter ideas are fraught with caveats and brings us full circle to where we were when Jeremy and I had our initial conversation 20 years ago.

If any of the methods could truly solve that last problem–comparing private equity returns directly to a limited partner other holdings–then they would be novel indeed. Otherwise these new approaches may simply be more branches on the PME family tree.

Thanks for reading

Jesse Reyes

Pingback: PME’s Volatility Noise | The DaRC Room